Prenatal stress

Many women know that experiences during pregnancy have long-term developmental consequences on child outcome. Education on how nutrition and environmental toxins, such as smoking and alcohol, affect the developing fetus is a part of routine prenatal care available to most women who are thinking of conceiving or who are expecting a child. Research emerging in recent decades has emphasized the importance of considering the role of stressors during pregnancy on short and long-term child development. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, physiological stress, and life events including living through natural disasters experienced by both the mother and father all effect child development. The impact of these factors spans a wide range of developmental periods and possible outcomes from physiological stress effects observed on increases in heart rate on the developing fetus, to increases in psychiatric symptoms in children during late adolescence.

In addition to including the findings from this line of work into routine prenatal care through education, there is now an emerging initiative to consider prenatal stressors as targets for intervention among clinical populations of expecting families. To add to this important line of work by increasing the precision of targets of intervention, is it part of the initiative of DREAMBIG to further understand the impact of prenatal stress on child development.

While our research is ongoing, here is some of what we know and don’t know about three important questions:

Question #1 : Is everyone affected by prenatal stress?

Not everyone is susceptible to the effects of prenatal stress. However, we are far from understanding who or what circumstances makes certain children more vulnerable. Factors such as genetics, parenting techniques, attachment, sex, and child temperament are just some of the many individual characteristics that have been consistently found to increase a child’s susceptibility to prenatal stress. We aim to understand if there are multiple mother or child characteristics that work together that may make some children more susceptible to prenatal maternal psychological stress.

Question #2 : What are the different kinds of stressors that we should be concerned about?

There has been a wide range of different types of stressors that have been found to contribute to child development from physiological factors such as cortisol that is produced by the body after encountering a stressful situation, to the situational factors like natural disasters and anxious or depressive symptoms that trigger these physiological reactions. Currently we do not know if there is a type of stress that is most important, if there are multiple stressors that have effects, or if there are some stressors that do not contribute to some developmental outcomes at all. Our current research aims to understand how different prenatal psychological symptoms experienced by the mother may have specific effects on outcomes of internalizing problems in childhood.

Question #3 : Is there a particular time during pregnancy that treatment might be most effective? Are effects the same for depressive symptoms after birth?

We still don’t know when during pregnancy exposure to stress could have the most harmful effects on child development. There is some research that indicates that the first trimester is the most important, while other research indicates that exposure during second and third trimester is most important in determining long term influences. It is very possible that exposure during certain trimesters are important for different types of outcomes. In terms of exposure to symptoms of depression after birth, effects of prenatal stress are hypothesized to be distinct occurring through biological pathways that cross the placenta. However, because in many cases prenatal stress influences postnatal depression, it is difficult to determine what developmental effects occur from exposure during pregnancy and what effects occur from exposure after pregnancy. Some research indicates that a cumulative effect of multiple times of exposure to stress is the most important, whereas other research indicates that there are distinct effects for prenatal and postnatal exposure and even interactive effects where neither prenatal or postnatal depression on their own effect development, but both together make an important contribution. Our research aims to understand more about how these different potential pathways of prenatal and postnatal maternal stress can impact child development.

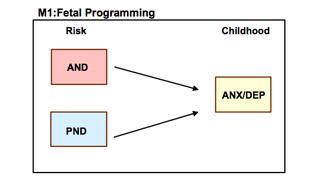

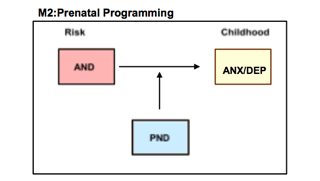

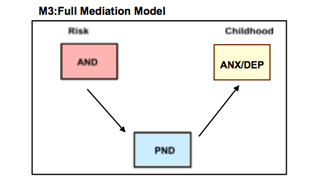

Figure showing the three possible pathways in which prenatal (AND) and postnatal (PND) depression can influence childhood symptoms of anxiety and depression. Fetal programming model hypothesizes prenatal and postnatal effects are distinct. Prenatal programming model hypothesizes the prenatal and postnatal effects interact. Full medication model hypothesizes a cumulative effect of prenatal and postnatal depression.

Genes

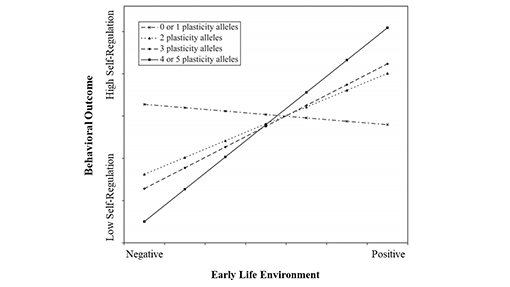

Many psychiatric disorders have been shown to be highly heritable, with 40-70% of mental disorders being transmitted from one generation to the next. Hereditary information is encoded via DNA and the genetic material that each of us inherits is a product of what we inherited from our parents with random genetic mutations also contributing to our genetic diversity. The pathway between a DNA sequence and an observable trait is complex and implies that not all children with a genetic predisposition go on to develop a psychiatric illness. Similarly, individuals with no genetic risk may still develop a mental health disorder; such individuals were likely exposed to adverse environmental conditions such as trauma, abuse or chronic stress. In most cases, a combination of environmental and genetic factors are the best predictors of developing mental illness. In other words, the manifestation of psychiatric disorders is a product of gene by environment interactions whereby the influence of genetic risk on psychopathology may only surface under certain environmental conditions. Moreover, several genes, as opposed to single genes, are likely responsible for the effect of this interaction on behavior. In fact, the more risk alleles (genetic susceptibility variants) a person has, the higher their likelihood of developing a mental health disorder. For example, possessing/carrying more risk alleles increases one’s chances of having a negative outcome (Belsky & Beaver, 2011). However, this relationship can be moderated (influenced) by environmental factors (Figure 1).

(Source: Belsky & Beaver, 2011)

Figure 1: In this context, plasticity alleles refer to susceptibility to both positive and negative environments (horizontal axis) in predicting behavioral outcomes such as emotional regulation (vertical axis). Depending on the environment and level of genetic risk, the probability of being high in emotional regulation increases the more plasticity alleles one has and the more positive one’s early life environment. Whereas those with little to no genetic risk seem to have the same moderate outcome regardless of their environment.

Figure showing the three possible pathways in which prenatal (AND) and postnatal (PND) depression can influence childhood symptoms of anxiety and depression. Fetal programming model hypothesizes prenatal and postnatal effects are distinct. Prenatal programming model hypothesizes the prenatal and postnatal effects interact. Full medication model hypothesizes a cumulative effect of prenatal and postnatal depression.

In addition, epigenetic regulation has been shown to be one of the main mechanisms driving fetal brain development – ‘programming’ neural networks according to cues the fetus is receiving from the external world. Since the fetal brain is in the beginning stages of formation, it is especially receptive and sensitive to incoming signals, making the prenatal period a critical developmental window. Again, these prenatal programming effects are adaptive and are intended to prepare the fetus for a similar postnatal environment. Despite the potential programming effects of the prenatal environment, the postnatal environment has a strong influence as well, holding the potential to override, reverse or strengthen prenatal effects.

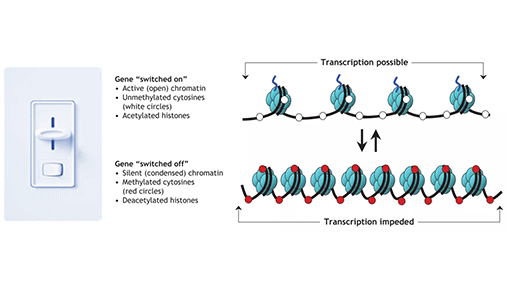

(Source: http://cnx.org/content/m26565/latest/graphics35.jpg)

Figure 2: There are several types of epigenetic mechanisms although the most studied mechanisms are DNA methylation and histone modifications, both of which influence chromatin structure. In the diagram above, DNA is wrapped around histones (blue spheres) while methylation marks are depicted by the red circles. Different combinations of histone proteins can alter chromatin state while methylation (addition of methyl groups) occurs in specific dinucleotide sequences (e.g., CpG context). Methylation and condensed chromatin typically make DNA inaccessible to transcription factors preventing gene expression. In some cases, epigenetic marks can turn a gene completely on or completely off while in other cases, epigenetic marks act more like a “dimmer”, adjusting the degree of gene expression. Various environmental or external factors can influence epigenetic activity, including stress, diet and exercise.

Therefore, when assessing a child’s likelihood for developing mental health problems, it is important to consider several interacting factors, namely prenatal influences, genetic susceptibility and level of stress exposure – as the expression of any human character is likely to depend on the action of a large number of gene and environmental factors. However, research attempts may not adequately capture the complexity of these interactions. For example, it is now known that mental disorders are not caused by a single gene, so using a single (candidate) gene approach undermines the influential role that multiple genes are having on behavior. On the other hand, genome-wide approaches (e.g., GWAS) are very exploratory in nature, require very large sample sizes and often turn up genes whose biological function is still unknown. Moreover, such genetic studies have proven difficult to replicate and do not consider how gene products are expressed. Not to mention, distinct observable traits (aka phenotypes) have been difficult to classify due to the presence of comorbidity (presenting with a range of symptoms associated with more than one disorder) as well as the subjectivity involved in diagnosing psychiatric disorders despite adhering to standard diagnostic guidelines. Finally, similar to single gene approaches, it is not informative to study a single environmental influences. Going forward, in order to have a better understanding of human behavior, it is necessary to simultaneously: 1) establish clear phenotypes, 2) investigate gene networks (whose function is known), 3) model multiple environmental influences, and 4) validate candidate gene studies using GWAS data and expression studies.

The role of the early postnatal environment in children’s psychological development

The early rearing environment has lasting effects on children’s psychological health and well-being. The brain develops at a rapid pace during the early years. Growing up in an adverse environment can disrupt this delicate, neatly orchestrated process, rendering children more vulnerable to develop behavioral and emotional problems in later life. Given that infants spend the majority of time with their mother, women have a central role in shaping their children’s early environment. Not surprisingly thus, much of the research in this field has focused on examining mothers’ sensitivity—that is, their ability to notice and adequately respond to their child’s needs—and how this affects children’s psychological development.

Researchers distinguish different parenting styles, such as sensitive parenting, harsh, coercive parenting or neglect. Negative parenting styles have the potential to increase the child’s risk for developing maladaptive behaviors. Additionally, they can also compromise the formation of the child’s first attachment relationship with their caregiver, which will serve as a schema for later intimate relationships.

Women who experience depression or other mental health problems during this period might find it particularly hard to be sensitive to their child’s needs. They thus might benefit from extra support from their partner, friends and family, larger social circle, daycare system and health care professionals.

The good news is that both parenting and psychological stress are amenable to change. For example, treating maternal depression has a beneficial effect for the mental health of both mothers and their children. Similarly, early interventions that target mothers’ parenting practices seem helpful in preventing or reducing problem behavior in their children. Such programs can be implemented either at the individual level or at the larger, community level.

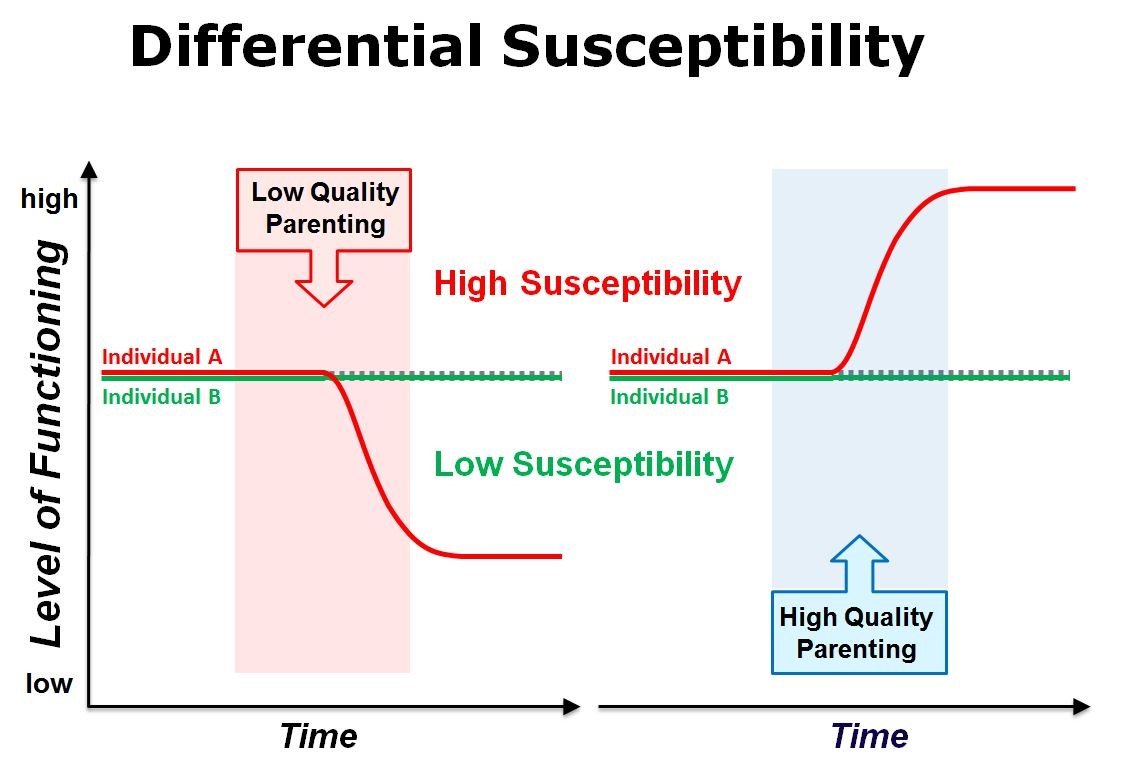

Evidence suggests that those children who are most affected by an adverse early environment are also the ones that benefit most from these interventions. This phenomenon is referred to as differential susceptibility and is illustrated by individuals A and B in the figure below.

Figure depicting differential susceptibility. The left-hand side of the figure shows that in the presence of low quality parenting individual A functions worse, while individual B is not affected. The right-hand side of the figure shows that when receiving high quality parenting, the level of functioning increases in individual A, whereas it remains unchanged in individual B. Individual A represents high susceptibility to the environment while individual B represents low susceptibility.

(Source: Pluess, M. & Belsky, J. (2012). Parenting effects in the context of child genetic differences. The Bulletin of the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development, 2(62), 2-5.)

We also want to understand what happens when individuals are resistant to the adverse effects of the environment (such as individual B on the left-hand side). What makes them resilient, are there other protective environmental factors at play or is it more due to the internal characteristics of the child?

Sex and gender

There are differences in how boys and girls are affected by mental illness. This is reflected, for example, by the higher rates of anxiety disorders and symptoms among girls and women compared to boys and men, and the higher rates of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder among boys compared to girls. Early life experiences have been proposed as contributing factors to child mental health problems. In particular, exposure to prenatal stress may help to explain gender differences in mental disorders.

Maternal stress during pregnancy may influence the developing fetus differently depending on gender. Prenatal stress has been associated with increased externalizing problems in boys, and increased internalizing problems in girls. Stress during pregnancy impacts males more significantly than females, such that boys whose mothers experience prenatal stress are more likely to have higher rates of autism, mental retardation, stuttering, dyslexia, and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. This increased vulnerability to developing neurodevelopmental problems among boys may be related to male fetuses being more sensitive to stress hormones throughout pregnancy. Female fetuses appear to respond well to prenatal adversity; however, this may be associated with consequences later on in life. Girls whose mothers experience prenatal stress are more vulnerable to developing internalizing problems such as anxiety and depression.

How such gender specific development vulnerability could be used to better focus prevention and early identification of psychopathology is a key objective of our research program.

References :

Bale, T. L. (2016). The placenta and neurodevelopment: sex differences in prenatal lvulnerability. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 18(4), 459.

Buss, C., Davis, E. P., Shahbaba, B., Pruessner, J. C., Head, K., & Sandman, C. A. (2012). Maternal cortisol over the course of pregnancy and subsequent child amygdala and hippocampus volumes and affective problems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(20), 1312-1319.

Davis, E. P., Buss, C., Muftuler, T., Head, K., Hasso, A., Wing, D., … & Sandman, C. A. (2011). Children’s brain development benefits from longer gestation. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 1.

McLean, C. P., & Anderson, E. R. (2009). Brave men and timid women? A review of the gender differences in fear and anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(6), 496-505.

Merikangas, K. R., Nakamura, E. F., & Kessler, R. C. (2009). Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(1), 7.

Park, J. H., Bang, Y. R., & Kim, C. K. (2014). Sex and age differences in psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents: high-risk students study. Psychiatry Investigation, 11(3), 251-257.

Quarini, C., Pearson, R. M., Stein, A., Ramchandani, P. G., Lewis, G., & Evans, J. (2016). Are female children more vulnerable to the long-term effects of maternal depression during pregnancy? Journal of Affective Disorders, 189, 329-335.

Zhu, P., Hao, J. H., Tao, R. X., Huang, K., Jiang, X. M., Zhu, Y. D., & Tao, F. B. (2015). Sex specific and time-dependent effects of prenatal stress on the early behavioral symptoms of ADHD: a longitudinal study in China. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(9), 1139-1147.